Reaching Agreement with Radical Candor

The first installment of "The Art of Agreement" series, featuring Kim Scott, best-selling author of Radical Candor.

The Art of Agreement is a series of unique perspectives from leaders and creators on the universal truths and tactics that get humans to agree. Check out the rest of the series:

The Art of Resolving Disputes - featuring Jennifer Lupo, Mediator

Using AI to Reach Agreement - featuring Martin Rand, CEO of Pactum

How do you give people feedback effectively? This might be the toughest challenge a manager faces, and it’s easy to get it wrong. Some managers don’t want to hurt people’s feelings. Some are too eager to be loved. Some are obnoxious, aggressive jerks. All of those approaches lead to disaster.

Kim Scott struggled with giving feedback when she was an executive and startup founder, which led her to develop a methodology for giving praise and criticism in a way that helps people learn and grow, while keeping team members motivated. Her 2017 bestseller, Radical Candor: How to Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity, has sold more than 1 million copies and become an invaluable guidebook for managers.

Scott honed her management skills at Google, then moved to Apple where she developed and taught a course on management. She has coached CEOs in Silicon Valley and now runs Radical Candor, offering feedback training, coaching, and consulting around the Radical Candor methodology, which involves “caring personally while challenging directly.”

Scott’s follow-up book, Radical Respect: How to Work Together Better, will be published in paperback in May.

This conversation was edited and condensed for clarity.

Is it fair to say that Radical Candor is about helping people agree?

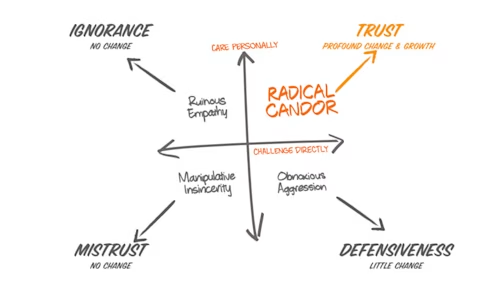

It's about getting to agreement. And the first thing I thought when you asked me to talk about the art of agreement is that agreement doesn't happen without disagreement, right? You're never going to get to agreement without disagreeing. If there are no disagreements, you have false harmony. It’s what I call ruinous empathy. A big part of a real agreement involves having some disagreements and resolving them.

So you begin by identifying the disagreements.

Or the potential disagreements. Let's say you and I are going to write a book together. We both want to write a book that's going to sell a ton of copies. What could go wrong, right? And then we think about, what's going to happen when I want to say A, and you want to say B, how are we going to resolve that? What's going to happen when I think we're finished, and you think we're not finished? Part of working well together is being able to anticipate those disagreements and figure out how you're going to resolve them in advance or have a method for resolving them as you go.

Is radical candor a way of getting there?

Radical candor is a way of saying, you and I are working together, I care about you, and because I care about you and I care about the work that we're doing together, I'm going to challenge you when I think you're wrong. That's what's going to help us get to an agreement.

You call it “caring personally while challenging directly.”

Exactly. That is how we're going to get to agreement. What happens if I fail to challenge you is that then we're either in ruinous empathy, in which I'm not telling you that I disagree, or I think you're wrong, but I don't want to hurt your feelings, so I don't tell you. That's not an agreement. So now we're working together, but we're starting to go in different directions. And we're not admitting it to each other.

It usually happens because I don't want to upset you. I don't want to offend you. I'm worried about your feelings. Or sometimes it’s what I call manipulative sincerity, where I’m worried about what you will think of me if I challenge you. Maybe I'm worried about retribution, that if I disagree with you that you'll punish me somehow. If I'm worried about myself, it's manipulative insincerity. If I'm worried about you and your feelings, it's ruinous empathy.

Then there’s what you call obnoxious aggression.

That’s where I challenge you, but I don't care about you. Very often it's the fear of being obnoxiously aggressive that causes us to be ruinously empathetic. I don't want to be judged, so I'm not going to say anything. And then you don't know what I'm really thinking, or you don't know about the mistake you're making.

In Radical Respect****, you write a lot about bias and discrimination in the workplace.

Radical respect is a culture that optimizes for collaboration, not coercion. I'm not going to try to force you to do things my way, but I'm going to work with you. It's more about partnership. And it's one that honors individuality. I'm going to accept you for who you are. I'm not going to tell you who you have to be to work with me. What gets in the way of radical respect? I call it a toxonomy. There's bias, prejudice, bullying, discrimination, harassment, and physical violations, and each of those things gets in the way of respect in different ways. Discrimination and harassment are different things, but we often conflate them.

When organizations hire you and your company to do workshops, what do they want to work on?

It’s all about feedback. They want to know how to give criticism. I convince them that you start by soliciting criticism. Then you give praise. And you give criticism that is sort of humble and helpful, gauge how it's landing, and adjust how you’re talking depending on how the other person responds. Being an authentic leader does not mean ignoring the impact you're having on others. You want to make sure that you are noticing, is the other person brushing you off? Then you need to move out further on the “challenge directly” dimension. Is the other person sad or mad? Then you need to move up on care personally. If somebody is mad at you, or yelling at you, it's kind of difficult to care personally, but that's the goal.

Are there some people who just can’t take criticism?

I think that everybody gets it. Everybody can deal with it. There are some people who don't have to deal with it because they have so much power. And that's where the real problem is. It's not oversensitivity that causes people to be unable to deal with feedback, it's too much power. They can get away with it. They can shut people up if they have power. Even if you have power within a small group. If you're a new manager and you have a few direct reports, you can shut them down for a while. It's sort of brutal incompetence. It works for a little while, and it hurts people. Before it doesn't work, it hurts people.

What happens when organizations don’t have radical candor?

At a certain level, you cannot get things done if you can't tell people when they're making mistakes. And if you can't solicit feedback. Especially if you have power in an organization, if you're a leader, you've got to learn how to solicit feedback. Because otherwise, if you're a leader, flattery comes at you like a thick, dangerous fog and you run aground before you know. If I don't reward the candor, I'm not going to get it, and then I make mistakes. And I don't know that I've made a mistake until it's too late. Andy Grove, when he was the CEO of Intel, said that being CEO is like you're at the center, but snow melts at the periphery, and you're going to be the last one to know that your iceberg has melted unless you're very proactive about rewarding people for telling you the truth. Another way of putting it came from Jim Morgan, who was the CEO of Applied Materials: “Good news is no news. And no news is bad news. And bad news is good news—if you do something about it.” Because you want to hear about mistakes you're making or problems that are happening.

So ruinous empathy and manipulative insincerity create stasis. You can’t get anything done.

With ruinous empathy, mistakes just get repeated and repeated and repeated, and you don't achieve results. But the problems may happen a little bit more slowly. With manipulative insincerity, you get real active distrust. Obnoxious aggression leads to defensiveness. It's like if you rub your dog's nose in poop, if you're house training them, they poop behind the rug, and that's even worse, right? So obnoxious aggression gets you defensiveness. Ruinous empathy gets you ignorance. And manipulative insincerity gets mistrust.

In addition to personal agreements, does Radical Candor apply when companies are negotiating agreements and making business deals?

A hundred percent. It’s hugely important. Any time you're trying to get something done with another human being, radical candor is essential. George Bernard Shaw said the biggest problem with communication is the illusion that it has happened. You think you have an agreement, but you don't have an agreement. And what happens between companies is that people think they have reached agreement, but they really haven’t.

Let's imagine that you really want me to give you an orange, and I really don't want to give you an orange. And you know that I don't really want to give you an orange, so you don't quite come out and ask for an orange. You don’t say, "Kim, do you commit to giving me an orange before February 28th?" Instead, you kind of say, "Ah, I really want an orange." And I kind of say, "Yeah, I know you really want an orange." So I don't say no, and you don't ask for a commitment. That is how agreements don't happen. And you walk out thinking, "Oh, Kim said she knows that I want an orange, so of course she's going to give it to me,” and believing that I'm going to give you an orange. And I walk out saying, "Well, I didn't promise him the orange, so thank goodness he knows I'm not going to give him the orange."

So we’ve both dodged the issue, and we don’t have an agreement.

Yes, and then you're really mad at me for not giving you the orange when you thought you were getting the orange, and I'm really mad at you for expecting an orange from me.

How do you fix that?

You have commitment conversations. Do you commit to giving me an orange by the 28th? And I say yes or no. My job is to give bad news early. Before you have asked me for the commitment, I probably know you want the orange. If I really care about you and I care about our relationship and I care about your ability to go get an orange from someone else, I'm going to come to you proactively and say, "Dan, I know you need an orange on the 28th. I want to tell you today, when it's only the 23rd, that I'm not going to give you an orange on the 28th.” Then you have time to ask someone else.

But when companies negotiate deals, don’t the lawyers pin everything down?

Well, I love lawyers. My father was a lawyer. But lawyers often obfuscate as much as they clarify. And I think that if two people are trying to work together and come to an agreement, what they need to do is drive the bus. It's important to tell your lawyers, "Look, you're going to tell me where the potholes are, but I'm driving the bus. I'm saying where we're going. You tell me what the risks are, and I tell you whether I'm willing to take the risks.” Sometimes we have a tendency to over-delegate to our lawyers. I don't want to tell you that I'm not going to give you the orange, or you don't want to insist on the orange, so we say, "Oh, our lawyers will work it out." And the lawyers don't even know. We haven't told our lawyers. Things get incredibly complicated. But if you and I talk and are very clear to our lawyers, we're going to save ourselves a lot of hassle. And we're going to have lower legal bills.

You write in Radical Candor that you weren't always good at giving feedback.

I struggled. It did not come naturally to me. I mean, I was raised as a girl in the South. I was raised never to disagree. What I learned is that when you never disagree, you wind up having worse disagreements than if you just sort it out. I really care about my relationships with people, and I really dislike conflict. But avoiding conflict creates bigger conflicts and more sort of yucky conflicts, for lack of a better word, than just saying, "You know what, Dan, I'm sorry, but I'm not going to give you that orange on the 28th."

How does someone who hates conflict learn to work up the courage to do that?

The thing that helped me more than anything else is to think about a couple of examples of it going well in my life and also to think about a couple of examples where it went really badly in my life, and to give those stories names. When I'm tempted to say, "Well, maybe I'll have an extra orange on the 28th,” to recognize that this is magical thinking and to realize that I am not being kinder to you if I choose not to tell you today. In fact, what I'm doing is being mean to you, because I'm depriving you of the next five days that you could go out and find other sources of oranges.

But we’re still in conflict, right?

The question is, do you want to have a small resolvable conflict now, or do you want to have a bigger conflict later in which you've done damage to your relationship, and you've left the person fewer degrees of freedom to solve their problem. Realizing that a small disagreement now is actually kinder to you and better for our relationship and better for our ability to get things done than avoiding it now and having a bigger problem later. It's like a stitch in time saves nine.

When did you start thinking about the concepts that went into Radical Candor****?

I probably started thinking about this when I was six years old. My grandmother was known for speaking her mind. And I had done something wrong. I don't even remember what I did. I probably told a lie. And she came down really hard on me. I was crying. She sat me down and said, "Kim, when people tell you you've made a mistake or you've done something wrong, if you can listen to it, you'll be better off in the long run. I said this thing because I love you and I want you to do better next time." And I remember going off to the bathroom in my parents' bedroom and thinking about what Granny had said and thinking, "Granny was right. I did tell a lie, and it's useful to understand why she told me this.”

Fast-forward 25 years, I've started a software company, and there's 60 people at the company, and one day 10 people email me the same article—about how employees would rather have a boss who's a total jerk but really competent than one who is really nice but incompetent. And I thought, "Are they sending me this because they think I'm a jerk, or because they think I'm incompetent?”

Which one was it?

Here was the mistake I made at that company, and I'm deeply ashamed of this mistake. I mean, I made a lot of mistakes, but I think the problem was that I was pretending to be nice, and the chair of the board of the company was really harsh. He was really mean. And I was allowing him to come in and be the jerk, but he was also not giving people the kind of feedback that they needed. I think I was being manipulatively insincere.

You wanted them to like you.

I wanted them to like me. Yeah. I really struggled with giving feedback as a leader. And I wondered, what's the way out? I don't want to be a jerk, but I also don't want to be incompetent. I learned a lot about this during my time at Google. But it was really when I went to Apple and I started developing and teaching this class, Managing at Apple—that was when I built the first two-by-two framework. Then I left Apple and I started writing Radical Candor. The original working title was Cruel Empathy. Because not giving feedback really is cruel in the end. But nobody liked the title. My husband, who's an engineer and very precise, hated it. And at the time I was coaching [Twitter founder and CEO] Jack Dorsey. I wanted him to read a draft of the book, but he refused. He said, "I'm not going to read any book called Cruel Empathy. I won't even read it until you come up with a better title."

I'm struck by how much humility plays a part in radical candor. You say that before you can give feedback, you need to be able to solicit feedback and accept criticism yourself.

It’s interesting. I had this debate on a podcast. There are a couple of people who I work with who really don't like the word humility, because it's so close to being humiliated, right? But I don't know a better word for being humble, being open to hearing about mistakes that you made. And to me, to be humble is also to be confident enough at the same time to reject some feedback that may be off base or incorrect. It's that combination of humility and confidence to solicit the feedback, and if you give someone feedback and they disagree with you, to be wide open to that disagreement. If you blow up when someone gives you bad news, and you sever all ties, then people are not going to give you bad news. They’re going to over-promise, but then they won’t deliver. The best thing a manager can do to build trust is to solicit feedback.

You write about former Google executive and Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, who would ask people after every meeting, “What could I have done better?”

Right, and it’s better to say it that way. Don’t say, “Is there anything I could have done better?” Because that’s a yes or no question. It’s better to say, “What could I do better? What could I stop doing that would make it easier to work with me?”

Does soliciting feedback also help when you’re making business agreements?

It’s hard when you're trying to come to an agreement, because if I'm trying to come to some kind of agreement with you, I have an agenda and you have an agenda. I don’t really want to hear about your agenda. But my willingness to understand what's going on for you might help us to come to an agreement. Let’s say you want an orange on the 28th and I can’t deliver that. But if I ask you, “Dan, what happens to you if I can’t deliver on the 28th,” you might tell me that what you really need is orange juice on the 29th. And it turns out that I have lots of orange juice, I just don't have any oranges.

Radical Candor is a business book, but do people ever tell you that it has helped them in their personal lives?

A hundred percent. All the time. Once I gave a talk and somebody came up to me and said, "If I had heard this five years ago, I wouldn't be divorced right now." I'm going to write a book about radical candor in the rest of your life. That combination of ruinous empathy and manipulative insincerity is so bad for relationships. The difference between radical candor at work and in your personal life is if I'm your friend and you're messing up, if I care about you, I'll tell you—but it's not my job. I'm not being paid to tell you you're messing up. But it still is kind of my obligation to tell you, if I care about you.

I would not be married if it weren't for radical candor. It's funny, but this happened when I first met Andy, who's now my husband, on the first time he spent the night at my house. I used to do yoga in the morning, so I went to the living room to do yoga, and he came in after me and sat down on the couch and started reading the New York Times. I didn't want him in the room reading the paper while I was doing yoga. I thought, “I never want to see him again. He's never coming over ever again." But then I was like, "Or I could just ask him to leave the room. And if that's not okay, then we never have to see each other again.” So I said, "I can't do yoga with you in the room," and he was like, "Oh, okay. I'm sorry," and he left. And I was like, "Oh, that wasn't so hard. I can see him again. We can have another date."

I keep thinking of my kids and the art of giving them feedback.

And you get it from them! Nobody in your life wants to give you feedback like your teenagers. That is a service they offer. And I have found that when I'm open to hearing it—that's why I delight in my teenagers, because I love to hear it. But writing that book has helped me be open to it.

Do you ever ask your kids some version of, "What can I do or stop doing that would make me a better parent?"

Yeah. Oh, yeah. And sometimes they'll tell me, "Let me stay up until 2:00 a.m. and give me infinite permission, and I’m like, "Nope, that's not going to happen. Try again." I don't have to agree with all their radical candor, thank heavens, but I do have to listen. I do have to be open to it.

Dan Lyons is an author and recovering journalist who has written about technology, work and business transformation.

Related posts

Docusign IAM is the agreement platform your business needs